Material Interventions into Immaterial Landscapes

Intervention I: Contemporary Artefact

Material Interventions into Immaterial Landscapes

Intervention I: Contemporary Artefact (Natural Gas Flare)

Postcards, Print, Website

Angela Anderson (2021)

This project was unrealizable in its proposed form within the timeframe of the Mutations residency program due to bureaucratic reasons on the side of the Linden Museum.

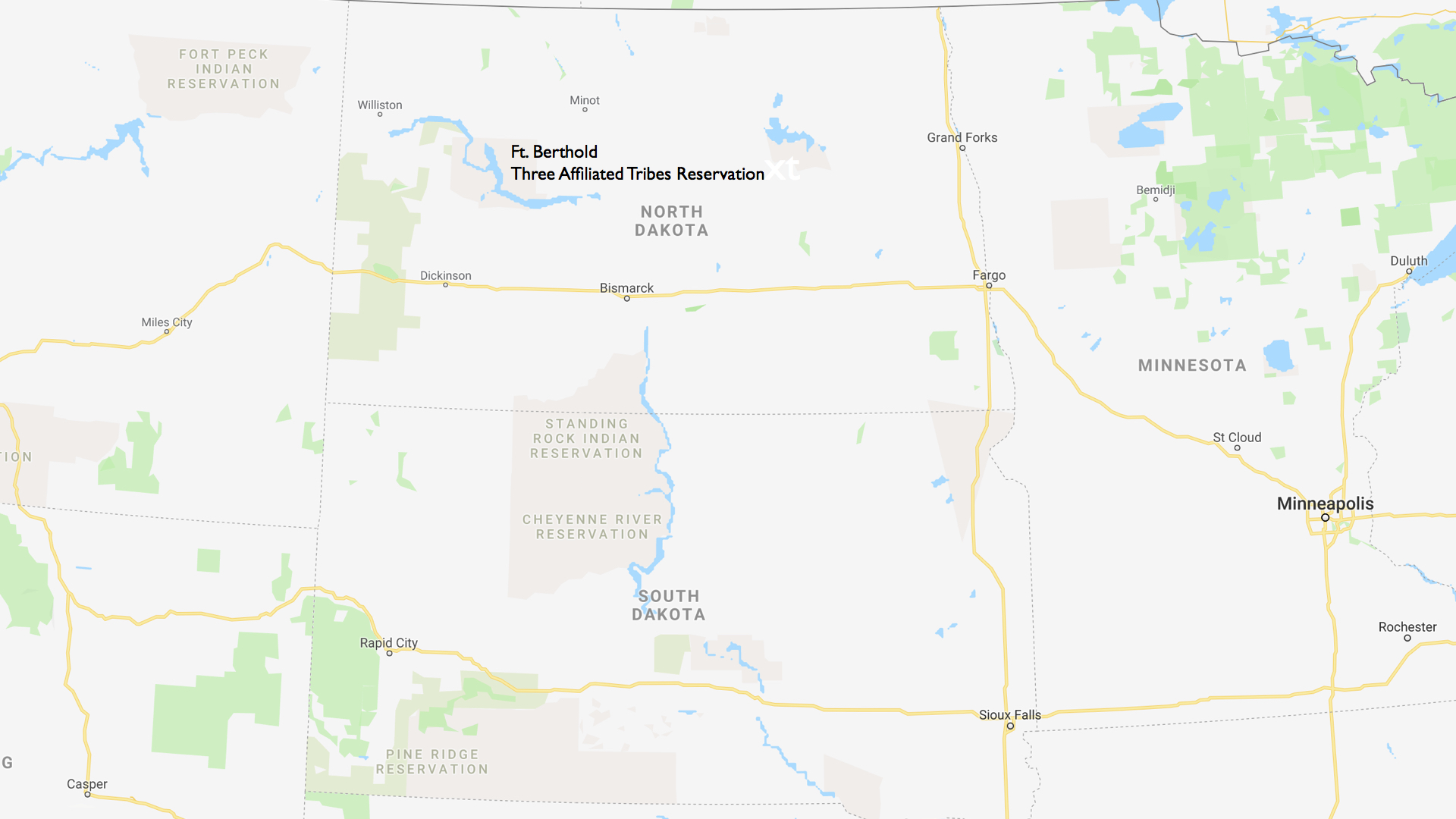

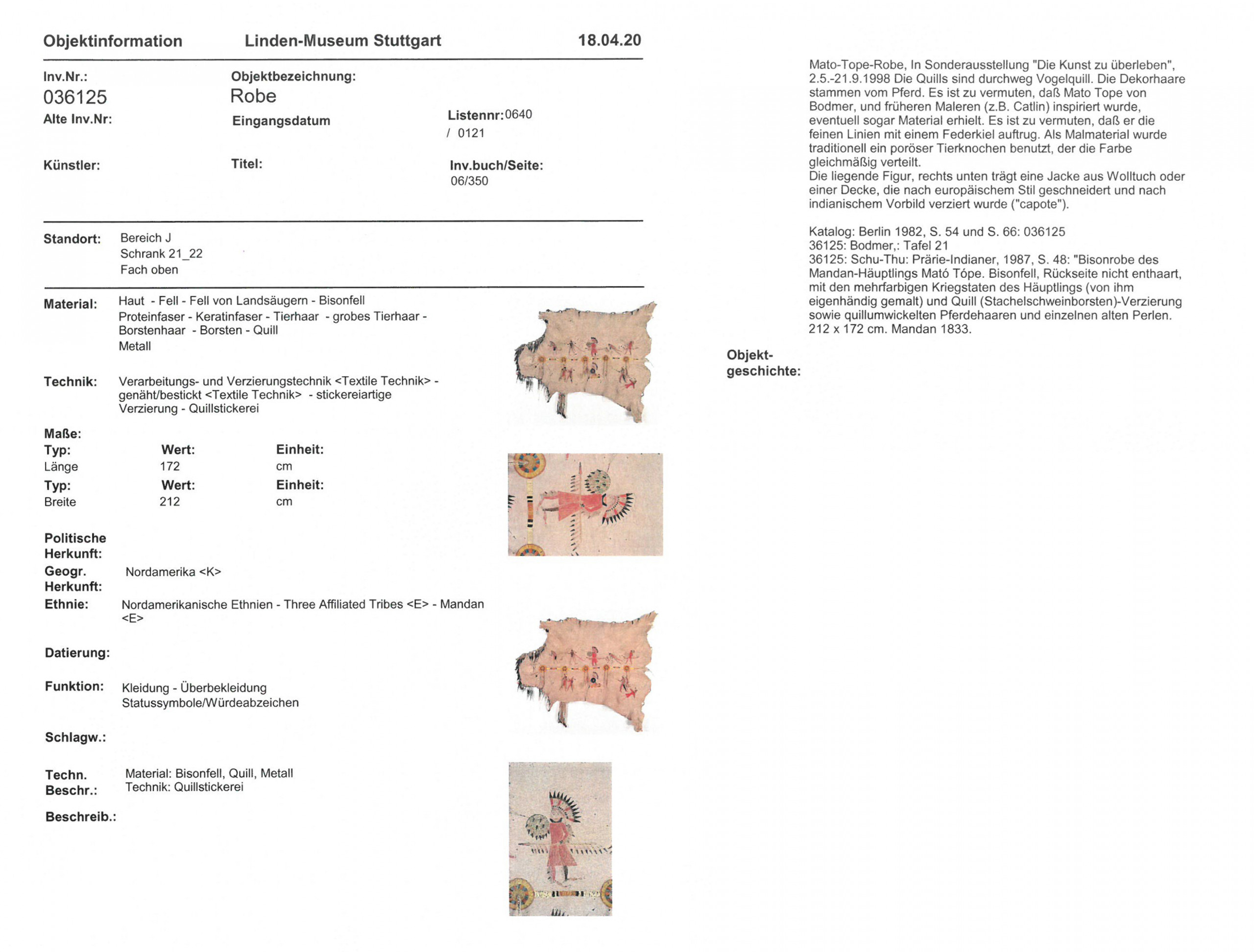

It was on the Ft. Berthold Reservation of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara nations that I first heard about the Linden Museum, an ethnographic museum in Stuttgart, as I was filming my recent video work, Three or More Ecologies - An Articulation of Feminist Eco-intersetionality, Part I: For the World to Live, Patriachy Must Die in March 2019. In particular, I was told about the robe of Mandan Chief Mato Tope (also known as Four Bears), which was given to Maximillian Prince of Wied-Neuwied, a german “explorer,” ethnologist and naturalist, in 1833, during his expedition on the Missouri River.

Wied-Neuwied’s substantial collection of artefacts from both North and South America are now part of the collections of several ethnographic museums in Germany and North America. A large part of the collection is housed in the Linden Museum, as well as the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. In North America, Wied-Neuwied travelled with the Swiss painter Karl Bodmer, who produced imagery of the people and landscapes they encountered, which demonstrate an artistic precision in the service of Western science, in the form of the European gaze and its effects of exocitization and othering. Original French language versions of his manuscript from Wied-Neuwied’s North American expeditions have recently sold on auctions by Christie’s and Sotheby’s for tens of thousands of dollars.

Archival description of Mato Tope’s Robe from the Linden Museum, 2020.

The memory of Mato Tope’s robe and its journey over the ocean to Germany is very much alive on Ft. Berthold today. In fact, one could say that part of the Three Affiliated Tribes is here in Stuttgart in spirit, as a living memory bridging past and future. The history experienced by the Mandan people since Chief Mato Tope’s robe left the Missouri river basin has been one of many hardships due to the onset of European settler colonialism. One of the most traumatic of these events happened in 1837, a mere four years after Mato Tope’s robe left for the shores of Europe, when 80 percent of the Mandan tribe died as a result of a smallpox epidemic, including Mato Tope.

U.S. officials and representatives of the Three Affiliated Tribes

(Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara) sign the Garrison Dam agreement on May 20, 1948. Secretary of the Interior Julius Krug writing his name while tribal chairman George Gillette sobs into his hand.

A century later, in 1953, after most of the traditional lands of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara (MHA) nations had been confiscated and given to European settlers, yet another traumatic event was visited upon the MHA Nation when the US government built the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River, as part of the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program, creating Lake Sakakawea, which intentionally flooded Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara villages and their best farmland.

Today, the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara nations finds itself in the heart of the Bakken shale oil formation, the second largest oil and natural gas producing region in the United States.

Chief Mato Tope’s robe exists at a major turning point of history in the Missouri river valley, and indeed for much of the territory west of the Mississippi river with the advance of European settler colonialism. Its existence forges a dynamic link to a historical moment when what we now know of as the United States had an entirely different history. To talk about Mato Tope’s robe is to talk about almost two hundred years of survival against all odds, in the face of repeated dispossession.

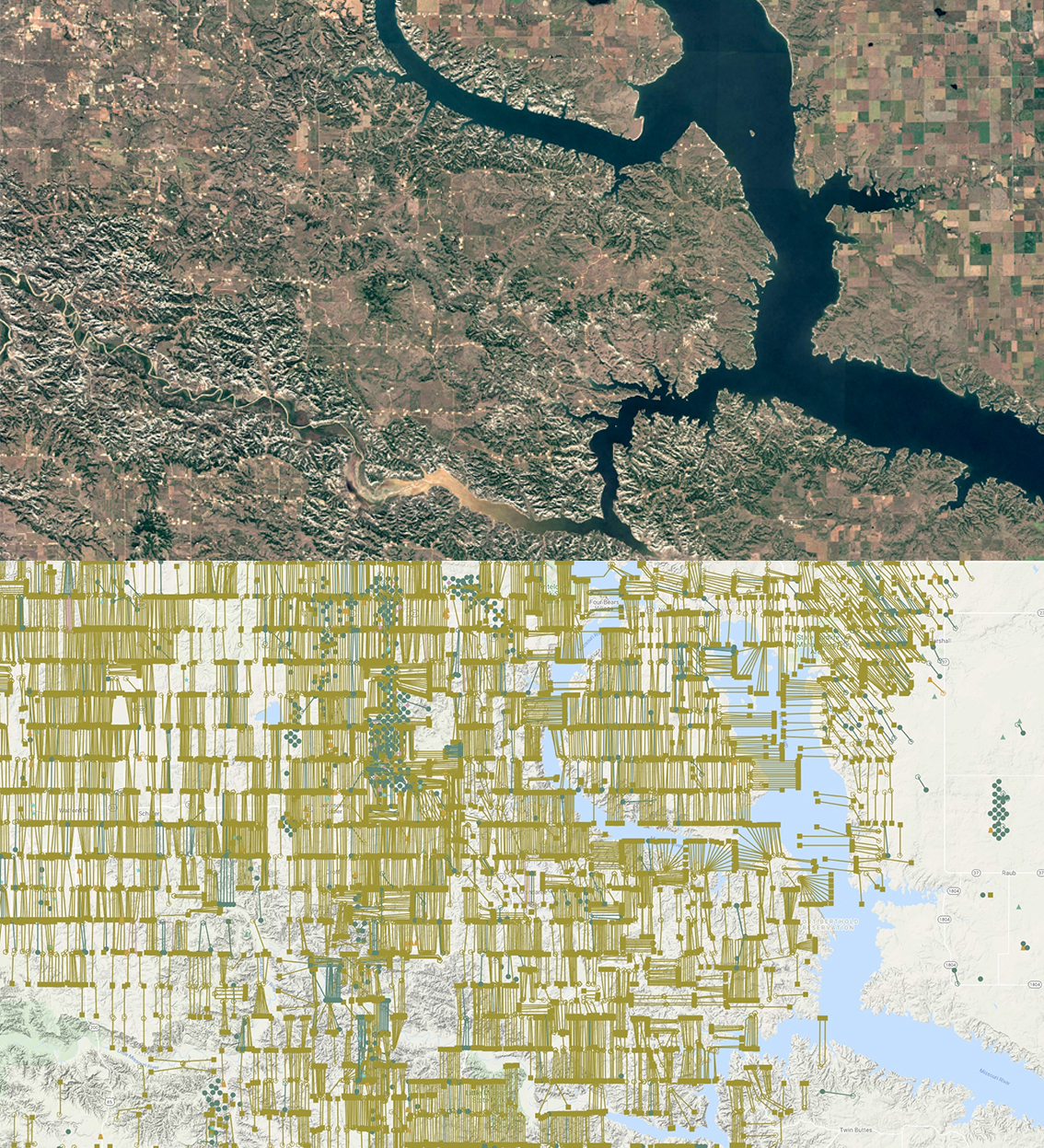

The current wave of oil extraction on the Ft. Berthold Reservation is very recent, beginning around 2007 as advances in the technology of hydraulic fracking allowed for the profitable extraction of oil from the Bakken Formation. At that historical moment, the Three Affiliated Tribes was in a difficult financial situation, and the oil industry presented itself as an easy path out. A decade after the first wells were drilled, one of the major environmental problems resulting from the oil extraction on the Ft. Berthold Reservation is the air pollution caused by the flaring of natural gas.

Natural gas flaring on the lands of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nations. As seen from the bluffs overlooking the Missouri River across from Four Bears Village, MHA Nation, March 2019. Photo: Angela Anderson

The burning off of natural gas has become standard business practice in the Bakken, because it is cheaper to burn off the gas than to install the infrastructure necessary to capture it. These flares burn day and night, with tremendous power. There is a visible layer of smog that hangs over parts of the reservation as a result. At night there are so many flares burning that the eastern part of North Dakota can now be seen from outer space. Because the oil industry brings a great deal of revenue to both the state government of North Dakota, there are very few environmental regulations and literally no monitoring of air quality.

Oil well in the North Dakota Badlands on lands of the MHA Nation, March 2019. Photo: Angela Anderson

One of the major critiques of anthropology, and by extension, ethnographic museums, is that their modes of representation and presentation connote a “denial of coevalness,” or in other words “a persistent and systematic tendency to place the referent(s) of anthropology in a Time other than the present of the producer of anthropological discourse.” 1 Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other – How Anthropology Makes its Object. Columbia University Press, New York. 1983. P.31 The pedagogical effects of this time-othering are multiple – ranging from racial stereotyping to the belief that certain cultural groups simply no longer exist.

Currently the Linden Museum is working to reframe the narrative presented through the objects in their collection, including through their current exhibition “Schweiriges Erbe” which takes a critical position towards the Linden Museum and Württemburg’s role in German colonialism, as well as through the exhibition “Wo ist Afrika?” which re-examines the museum’s collection of objects from the African continent acquired during the colonial period.

It was with this in mind that I proposed to give another object to the Linden Museum, a modern artefact from the present-day Ft. Berthold Reservation, in the form of an artistic intervention. I proposed to give the museum a natural gas flare, one of the most ubiquitous objects now found on the land that Chief Mato Tope once called home. This artefact was intended as a dialogue opener around the subjects of memory, care-taking, and modes of relation in a post-colonial world, and as a way of making explicit the legacies of and connections between the colonial collecting of artefacts and large-scale natural resource extraction. The fact that automotive industry makes up such a large part of the economy of Stuttgart and Baden-Württemberg (both Daimler and Porsche have their headquarters here) adds yet another layer of complexity with regards to the question of who profits from and who must live with the impacts of natural resource extraction and subsequently climate change.

The gas flare would have been installed on loop on a LCD screen (this was the preferred version) or as a print of a still image, installed in a similar way as the current visual elements on the façade, for the duration of the Mutations exhibition. On ground level there would have been a sign with the title of the work, as well as a QR code linking to this project website.

Unfortunately this project was unrealizable in its proposed form within the timeframe of the Mutations residency program due to bureaucratic reasons on the side of the Linden Museum.

For more about the situation and effects of the Bakken shale oil boom on the MHA Nation, see the section Reports from an Extraction Zone in the most recent edition Academy Schloss Solitude Journal, which was edited by fellows of the Mutations thematic residency.